The Comprehensive History of Dynamic Websites

From Static Pages to Modern Web Applications

TL;DR Summary

Dynamic websites evolved from simple CGI scripts in 1993 to complex web applications powered by modern architectures. The journey progressed through server-side technologies (Perl, PHP, ASP, JSP), client-side innovations (JavaScript frameworks), and architectural shifts (LAMP to MEAN to JAMstack). Today's dynamic web leverages serverless computing, microservices, WebAssembly, and AI-driven components, enabling real-time interactions, personalization, and edge computing capabilities that blur the line between web and native applications.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 2. The Birth of the Dynamic Web (1991-1995) 3. Server-Side Revolution (1995-2000) 4. Database-Driven Web (1995-2005) 5. Client-Side Evolution (1995-2010) 6. Web 2.0 & AJAX Revolution (2005-2010) 7. Modern Frontend Frameworks (2010-Present) 8. Modern Backend Architectures (2010-Present) 9. Database Evolution in Dynamic Websites 10. Modern Web Architectures 11. Mobile & Responsive Web 12. Real-time Web Technologies 13. Future Trends in Dynamic Websites 14. Frequently Asked Questions 15. Key Takeaways and Conclusion 16. About the Author1. What Is the History and Evolution of Dynamic Websites?

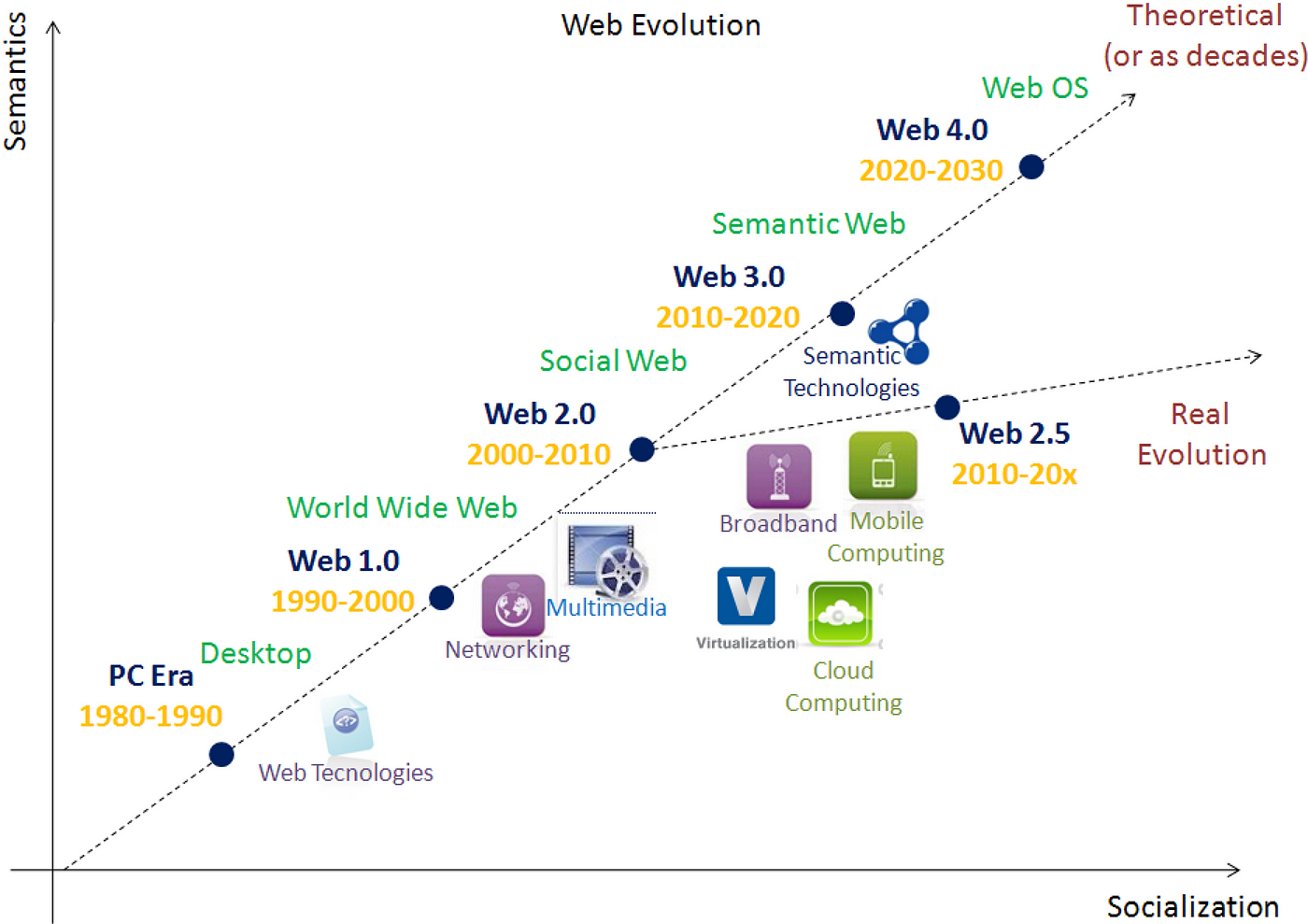

Dynamic websites have revolutionized how we interact with the digital world. Unlike their static predecessors, which displayed fixed content, dynamic websites generate content in real-time based on user interactions, data inputs, and contextual information. This evolution has transformed the web from a collection of simple text documents to a platform for sophisticated applications that rival desktop software in functionality and user experience.

The journey from static to dynamic web spans over three decades, marked by technological innovations, architectural paradigms, and shifting development practices. At each stage, new capabilities enabled more interactive, personalized, and functional web experiences. Understanding this evolution provides crucial context for modern web development and offers insights into future directions of the field.

Dynamic websites represent a fundamental shift in how we conceive the web—from an information medium to an application platform. This transformation has democratized software distribution, enabled global-scale services, and created new business models that power much of the modern digital economy [Pingdom].

This guide traces the technical evolution of dynamic websites from their inception to the present day and explores emerging trends that will shape their future. By examining key technologies, architectural patterns, and development approaches, we'll provide a comprehensive understanding of how the web has become the dynamic, interactive platform we know today.

2. How Did the Dynamic Web Begin? (1991-1995)

The web began as a static medium. When Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web in 1989-1991 at CERN, his system consisted of three fundamental technologies: HTML (Hypertext Markup Language), HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), and URLs (Uniform Resource Locators). The first websites were simple HTML documents linked together through hyperlinks, serving as static information repositories [CERN].

When Did Static HTML Pages First Appear?

The first-ever website, created by Tim Berners-Lee in 1991, was a simple HTML page explaining the World Wide Web project. This and other early websites were entirely static—their content remained unchanged until someone manually edited the HTML files. Each page was a separate document, and navigation occurred through explicit links between these documents.

Static HTML pages had significant limitations. Content updates required direct editing of HTML files, making frequent updates impractical for large sites. Different users saw identical content, with no personalization. Interactive features were extremely limited, typically restricted to hyperlinks and basic form submissions that required server processing and complete page reloads.

How Did Common Gateway Interface (CGI) Transform the Web?

The birth of the truly dynamic web can be traced to 1993 with the introduction of the Common Gateway Interface (CGI). CGI defined a standard way for web servers to interact with external programs, allowing websites to execute scripts and return their output as HTML to users. This breakthrough enabled servers to generate dynamic content on the fly rather than serving pre-written HTML files [Pingdom].

Perl became the dominant language for CGI programming due to its excellent text-processing capabilities and widespread availability. A typical CGI program would:

- Receive input data from user form submissions

- Process this data, often interacting with databases or other systems

- Generate HTML output dynamically based on the processed data

- Return this HTML to the web server, which would then send it to the user's browser

1991: The First Website

Tim Berners-Lee launches the first website at CERN, consisting of static HTML pages explaining the World Wide Web project.

1993: CGI Specification

The Common Gateway Interface specification is developed at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), enabling the first interactive web applications.

1993-1994: Perl as CGI Language

Perl emerges as the dominant language for CGI programming, powering the first generation of dynamic websites.

1994: First Web Forms

HTML 2.0 introduces forms, greatly expanding the possibilities for user input and interactive web applications.

Early Dynamic Web Use Cases

- Guestbooks: Allowing visitors to leave comments that would appear on the website

- Hit Counters: Displaying the number of visitors to a page

- Form Processors: Handling submissions from contact forms and surveys

- Search Functionality: Enabling users to search website content

- Basic E-commerce: Processing simple orders and payments

While revolutionary, CGI had significant limitations. Each request spawned a new process on the server, making it resource-intensive and slow for high-traffic websites. The need to generate complete HTML pages for every interaction limited interactivity. These limitations would drive the development of more efficient server-side technologies in the years that followed.

3. How Did Server-Side Technologies Revolutionize the Web? (1995-2000)

The late 1990s saw an explosion of server-side technologies that addressed CGI's limitations and significantly expanded the capabilities of dynamic websites. These technologies made it easier to create dynamic content, handle larger volumes of traffic, and build increasingly sophisticated web applications.

What Made PHP a Game-Changer for Dynamic Websites?

PHP (originally Personal Home Page, later PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor) was created by Rasmus Lerdorf in 1994 and released publicly in 1995. It represented a fundamental shift in how dynamic websites were created. Unlike CGI scripts, which were separate programs invoked by the web server, PHP code could be embedded directly within HTML documents using special tags (). This approach made it much more intuitive for web developers to mix static and dynamic content.

PHP's simplicity, combined with its features specifically designed for web development, led to explosive growth in its adoption. By embedding processing logic directly in web pages, PHP eliminated the need to write separate programs for generating HTML, making development faster and more accessible. The language's easy database connectivity, particularly with MySQL, enabled the rapid development of database-driven websites [Pingdom].

<html>

<head><title>PHP Example</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, <?php echo $_GET['name'] ? $_GET['name'] : 'World'; ?>!</h1>

<p>The current time is: <?php echo date('Y-m-d H:i:s'); ?></p>

</body>

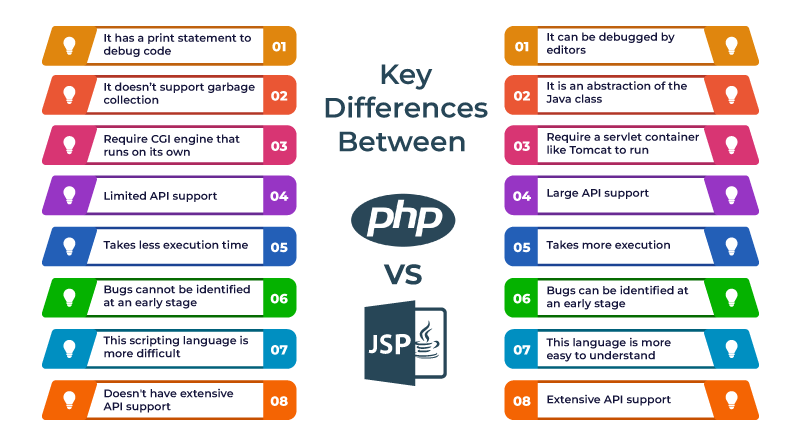

</html>How Did Microsoft's ASP and Sun's JSP Compete in the Enterprise Space?

As the web grew in commercial importance, enterprise-focused solutions emerged. Microsoft introduced Active Server Pages (ASP) in 1996 as part of its Internet Information Services (IIS) web server. ASP allowed developers to use VBScript or JScript (Microsoft's JavaScript implementation) for server-side scripting, with tight integration with other Microsoft technologies.

Sun Microsystems (now Oracle) developed JavaServer Pages (JSP) in 1999 as part of its Java Enterprise Edition platform. JSP allowed Java code to be embedded in HTML, similar to PHP, but with the full power and object-oriented structure of the Java language. JSP offered robust enterprise features like transaction management, security, and scalability that appealed to large organizations and mission-critical applications [Wikipedia].

What Role Did ColdFusion Play in Simplifying Dynamic Web Development?

Allaire Corporation (later acquired by Macromedia and then Adobe) released ColdFusion in 1995. ColdFusion introduced a unique tag-based approach to server-side scripting with its ColdFusion Markup Language (CFML). This approach made it particularly accessible to web designers familiar with HTML but without traditional programming experience.

ColdFusion's integrated development environment and built-in functionality for common web tasks (database access, email, file manipulation) made it possible to create sophisticated applications with minimal code. Its focus on rapid application development made it popular for business applications where development speed was prioritized [Adobe].

Comparing Early Server-Side Technologies

| Technology | Year | Language | Key Advantages | Notable Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGI/Perl | 1993 | Perl, C, others | Platform independence, versatility | Early interactive forms, guestbooks |

| PHP | 1995 | PHP | Easy to learn, HTML embedding, MySQL integration | WordPress, Facebook (early version) |

| ASP | 1996 | VBScript, JScript | Microsoft ecosystem integration, Windows-optimized | Enterprise intranets, .NET applications |

| ColdFusion | 1995 | CFML | Rapid development, tag-based syntax | Business applications, NASA websites |

| JSP | 1999 | Java | Enterprise features, scalability, security | Banking applications, government systems |

These server-side technologies transformed web development by making dynamic content creation more efficient and accessible. They enabled more complex applications like e-commerce sites, content management systems, and web portals that would become ubiquitous in the following years. The competition between these technologies drove rapid innovation, with each platform adopting successful features from its rivals.

4. How Did Databases Transform Dynamic Websites? (1995-2005)

As dynamic websites evolved, they increasingly relied on databases to store and retrieve content, user information, and application data. This integration of databases with web technologies enabled far more sophisticated applications and laid the foundation for the modern web.

Why Was the LAMP Stack Revolutionary for Web Development?

The LAMP stack—Linux (operating system), Apache (web server), MySQL (database), and PHP (programming language)—emerged in the late 1990s as a powerful, open-source platform for building dynamic websites. The term was coined by Michael Kunze in 1998 and popularized by O'Reilly Media in the early 2000s [Tedium].

The LAMP stack was revolutionary for several reasons:

- Cost-effectiveness: All components were free and open-source, dramatically reducing the barrier to entry for web development compared to proprietary alternatives.

- Integration: The components worked seamlessly together, with PHP offering native MySQL connectivity and optimized Apache integration.

- Scalability: The stack could power everything from small personal websites to massive platforms serving millions of users.

- Community: A large ecosystem of developers, documentation, and extensions made learning and extending the stack accessible.

The LAMP stack democratized web development, enabling individuals and small organizations to build sophisticated web applications that previously required significant resources. It powered many of the websites that defined the early dynamic web, including early versions of Facebook, WordPress, Wikipedia, and countless forums, blogs, and e-commerce sites [Tedium].

/uploads/1001_lamp.jpg)

How Did Content Management Systems Change Website Development?

Content Management Systems (CMS) represented the next evolution in dynamic websites, building on the foundation of server-side scripting and database integration. Early CMSs like PHPNuke (2000), Drupal (2001), and WordPress (2003) separated content creation from technical implementation, allowing non-technical users to manage websites through user-friendly interfaces.

These systems stored content in databases and used templates to determine how that content would be displayed, creating a clear separation between content and presentation. This approach offered several advantages:

- Content could be updated without technical knowledge or HTML editing

- Multiple authors could contribute content through controlled workflows

- The same content could be presented in different formats or contexts

- Site-wide changes to design or functionality could be implemented without affecting content

WordPress, in particular, transformed the web publishing landscape. Starting as a simple blogging platform, it evolved into a full-featured CMS that today powers over 40% of all websites on the internet. Its plugin and theme architecture allowed for extensive customization while maintaining a user-friendly interface, making dynamic website creation accessible to millions of non-technical users [WPBeginner].

What Role Did SQL Play in the Rise of Dynamic Websites?

Structured Query Language (SQL) and relational databases became fundamental to dynamic websites, providing a standardized way to store, retrieve, and manipulate structured data. MySQL, released in 1995, became particularly dominant in web development due to its speed, reliability, and tight integration with PHP.

SQL databases enabled several critical capabilities for dynamic websites:

- User management: Storing user accounts, preferences, and authentication data

- Content storage: Managing articles, products, media, and other website content

- Relationships: Modeling connections between different types of data (e.g., authors and articles)

- Transactions: Ensuring data integrity during complex operations like e-commerce purchases

- Searching and filtering: Enabling users to find specific content within large datasets

The integration of databases transformed websites from simple collections of pages into sophisticated applications with dynamic content, user accounts, and interactive features. This database-driven approach remains fundamental to most dynamic websites today, though the specific database technologies have diversified beyond traditional SQL systems.

Database-Driven Applications That Defined an Era

- Forums and Message Boards: vBulletin, phpBB, and Invision Power Board enabled online communities with threaded discussions, user profiles, and moderation tools.

- E-commerce Platforms: osCommerce and later Magento provided database-driven product catalogs, shopping carts, and order management.

- Wikis: MediaWiki (powering Wikipedia) created collaborative knowledge bases with version history and user contributions.

- Blogs: WordPress, Movable Type, and Blogger made personal and professional publishing accessible through database-backed content management.

This era of database-driven websites laid the groundwork for the social media platforms, e-commerce giants, and content-rich experiences that would define Web 2.0. The fundamental patterns established during this period—separating data, presentation, and logic—continue to influence web architecture today, even as the specific technologies have evolved.

5. How Has the Client Side of Dynamic Websites Evolved? (1995-2010)

While server-side technologies were rapidly advancing, equally important changes were happening on the client side. The evolution of JavaScript and browser capabilities progressively shifted more functionality from servers to browsers, fundamentally changing how dynamic websites operated and what they could achieve.

When Was JavaScript Introduced and How Did It Impact Dynamic Websites?

JavaScript was created by Brendan Eich at Netscape in just 10 days in May 1995. Originally named Mocha, then LiveScript, it was finally renamed JavaScript—partly for marketing reasons due to the popularity of Java, despite being an entirely different language. JavaScript was designed to add interactivity to web pages by allowing code to run directly in the browser [GeeksforGeeks].

The initial version of JavaScript was limited in scope, primarily used for basic form validation and simple interactions like rollover effects. However, it represented a crucial shift in web development paradigms by enabling:

- Client-side validation, reducing server round-trips for basic form checking

- Dynamic HTML manipulation, allowing content to change without page reloads

- Enhanced user interfaces with interactive elements responding to user actions

- Basic animations and visual effects to improve engagement

JavaScript's adoption was accelerated by the "browser wars" between Netscape Navigator and Microsoft Internet Explorer, as both browsers competed to add support for more advanced scripting capabilities. This competition, while creating cross-browser compatibility challenges, drove rapid innovation in client-side technologies.

What Was the Document Object Model (DOM) and Why Was It Important?

The Document Object Model (DOM) emerged as a standardized way to represent and interact with HTML documents. Formalized by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in 1998, the DOM provided a structured, object-oriented representation of web documents that could be modified with JavaScript.

The DOM was revolutionary because it transformed HTML from a static document format into a dynamic, programmable interface. It allowed JavaScript to:

- Access and modify page content after it had loaded

- Create new HTML elements dynamically

- Respond to user events like clicks, keystrokes, and mouse movements

- Change styles and attributes of page elements on the fly

- Create rich, interactive interfaces within the browser

This capability fundamentally changed how dynamic websites could function. Instead of requiring server round-trips for every interaction, many updates could happen directly in the browser, creating more responsive user experiences [MDN Web Docs].

1995: JavaScript Created

Brendan Eich develops JavaScript at Netscape, enabling client-side interactivity in web browsers.

1996: Internet Explorer 3.0

Microsoft introduces JScript, their JavaScript implementation, intensifying browser competition and scripting capabilities.

1998: DOM Level 1

W3C standardizes the Document Object Model, providing a platform-neutral interface for manipulating HTML documents.

2000: DHTML Becomes Popular

Dynamic HTML (combination of HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and DOM) enables more interactive web experiences.

2005: Early JavaScript Libraries

Prototype.js, Script.aculo.us, and other libraries emerge to simplify DOM manipulation and add visual effects.

What Challenges Did Early Client-Side Development Face?

Despite its potential, early client-side development faced significant challenges:

- Browser inconsistencies: Different browsers implemented JavaScript and the DOM in incompatible ways, requiring complex workarounds and browser detection.

- Performance limitations: Early JavaScript engines were relatively slow, limiting the complexity of client-side applications.

- Accessibility concerns: Many JavaScript-enhanced features were inaccessible to users with disabilities or those using assistive technologies.

- Security vulnerabilities: Cross-site scripting (XSS) and other security issues emerged as client-side scripting became more powerful.

- Development complexity: The lack of standardized tools and frameworks made sophisticated client-side development challenging and error-prone.

These challenges would be addressed in the years that followed, with browser standardization efforts, performance improvements, accessibility guidelines, security best practices, and the development of libraries and frameworks to simplify JavaScript development. The groundwork laid during this period would enable the more sophisticated client-side applications that would emerge in the AJAX era and beyond.

6. How Did AJAX and Web 2.0 Transform Dynamic Websites? (2005-2010)

The mid-2000s saw a transformative shift in how dynamic websites functioned, primarily driven by AJAX technology and the broader Web 2.0 movement. This period marked the evolution from page-based websites to more application-like experiences with richer interactivity.

What Is AJAX and How Did It Change Web Interaction?

AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) represented a collection of techniques that allowed web pages to communicate with servers in the background without requiring full page reloads. The term was coined by Jesse James Garrett in 2005, though the underlying technologies had existed for several years, most notably with Microsoft's XMLHttpRequest object introduced in Internet Explorer 5 in 1999 [W3Schools].

AJAX fundamentally changed how users interacted with websites by:

- Eliminating complete page reloads: Updates could occur within specific parts of a page without disrupting the overall user experience.

- Enabling background data loading: Content could be fetched asynchronously while users continued to interact with the page.

- Creating more responsive interfaces: Interactions felt more immediate and fluid, similar to desktop applications.

- Supporting continuous interactions: Complex interfaces like drag-and-drop, infinite scrolling, and live updates became possible.

// Basic AJAX request example (circa 2005)

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("GET", "data.php", true);

xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (xhr.readyState == 4 && xhr.status == 200) {

document.getElementById("result").innerHTML = xhr.responseText;

}

};

xhr.send();What Defined the Web 2.0 Era of Dynamic Websites?

The term "Web 2.0" was popularized by Tim O'Reilly and Dale Dougherty in 2004 to describe the web's evolution from a collection of static websites to a platform for interactive applications and user-generated content. While not a specific technology, Web 2.0 represented a conceptual shift in how the web was used and developed [Investopedia].

Key characteristics of Web 2.0 included:

- Participation: Websites shifted from one-way publishing to platforms where users could contribute content (blogs, wikis, social media).

- Rich user experiences: AJAX and improved JavaScript capabilities enabled more sophisticated, application-like interfaces.

- Data-centric approach: Websites became increasingly focused on managing and displaying large datasets rather than static content.

- APIs and mashups: Services began exposing APIs that allowed developers to combine data and functionality from multiple sources.

- Social features: User profiles, connections, and interactions became central to many platforms.

Which Pioneering Applications Defined This Era?

Several groundbreaking applications demonstrated the power of AJAX and Web 2.0 principles, setting new standards for what was possible in a web browser:

Web 2.0 Pioneers

| Application | Launch | Innovation | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Google Maps | 2005 | Smooth panning and zooming with asynchronous tile loading | Demonstrated that complex, desktop-like interactions were possible in browsers |

| Gmail | 2004 | Rich email interface with background loading and updating | Proved web applications could replace desktop software for critical tasks |

| Flickr | 2004 | Tag-based organization, comments, and dynamic photo management | Pioneered social features and user-generated content organization |

| 2004 | News feed with dynamic updates and social interactions | Established patterns for social networking applications | |

| 2006 | Real-time updates and infinite scrolling | Popularized real-time web and stream-based interfaces |

These applications showcased what was possible with the new paradigm of web development. They combined server-side technologies with client-side AJAX techniques to create experiences that were previously unimaginable on the web, establishing patterns that continue to influence web application design today.

The AJAX revolution fundamentally changed user expectations for websites. Static pages and full reloads became increasingly outdated as users came to expect the responsiveness and interactivity pioneered by these applications. This shift drove further advances in browser capabilities, JavaScript performance, and development tools to support increasingly sophisticated web applications [CodeTV].

7. How Have Modern Frontend Frameworks Changed Web Development? (2010-Present)

As web applications grew increasingly complex, developers needed better tools to manage client-side code. This need gave rise to JavaScript frameworks and libraries that fundamentally changed how dynamic websites are built and structured.

Why Did jQuery Become So Important for Web Development?

Released in 2006 by John Resig, jQuery became the most widely used JavaScript library in the world. Its motto, "Write less, do more," encapsulated its appeal—jQuery simplified complex JavaScript tasks and normalized browser inconsistencies through an elegant API. At its peak, jQuery was used by more than 70% of the top 10 million websites [pzuraq].

jQuery's key contributions included:

- Simplified DOM manipulation: Selecting and modifying elements became dramatically easier with its CSS-like selectors.

- Cross-browser compatibility: jQuery handled browser differences internally, allowing developers to write code once that worked everywhere.

- Ajax simplification: Complex XMLHttpRequest code was reduced to simple method calls.

- Animation and effects: Visual transitions became easy to implement with built-in animation methods.

- Extensibility: A robust plugin architecture enabled thousands of community extensions.

// jQuery example showing its simplicity

// Vanilla JavaScript equivalent would be much longer

$(document).ready(function() {

$("#loadData").click(function() {

$.ajax({

url: "data.json",

success: function(result) {

$(".result").html(result);

$(".result").fadeIn(500);

}

});

});

});jQuery bridged the gap between the early, primitive JavaScript era and modern frameworks. It demonstrated the power of abstraction and established patterns for DOM manipulation and event handling that influenced all subsequent frameworks.

What is the Significance of Angular, React, and Vue.js?

Around 2010-2013, a new generation of JavaScript frameworks emerged that completely reimagined how web applications should be structured. These frameworks brought concepts from software engineering that had previously been rare in front-end development [Primal Skill Programming]:

The Three Most Influential Modern JavaScript Frameworks

Angular

Developed by Google and released in 2010 (as AngularJS, later reimagined as Angular), this framework introduced a comprehensive approach to building single-page applications with two-way data binding, dependency injection, and a component-based architecture. Angular brought full MVC (Model-View-Controller) architecture to the browser and encouraged a highly structured approach to application development. Its opinionated nature made it particularly popular for enterprise applications where consistency and maintainability were prioritized.

React

Created by Facebook and released in 2013, React introduced the revolutionary concept of a virtual DOM and a component-based architecture focused on one-way data flow. Unlike Angular's full-framework approach, React positioned itself as a library focused specifically on building user interfaces. Its innovation of reconciling changes through a virtual DOM before updating the actual DOM dramatically improved performance for complex, data-driven interfaces. React's component model, with its emphasis on small, reusable pieces, fundamentally changed how developers structure web applications.

Vue.js

Created by Evan You and released in 2014, Vue combined elements from both Angular and React into a progressive framework that could be adopted incrementally. It offered two-way data binding like Angular but with a lighter footprint, and a component-based architecture like React but with a gentler learning curve. Vue's emphasis on simplicity and flexibility made it particularly popular with developers looking for a middle ground between Angular's structure and React's flexibility.

How Did Declarative UI and Component Architecture Transform Web Development?

Modern frameworks introduced two key paradigms that fundamentally changed how dynamic websites are built [MDN Web Docs]:

-

Declarative UI: Instead of directly manipulating the DOM (imperative approach), developers now describe what the UI should look like based on the current state, and the framework handles the DOM updates. This approach makes code:

- More predictable, as the UI is always a function of the current state

- Easier to reason about, as developers don't need to track DOM manipulation sequences

- More maintainable, with clearer relationships between data and its visual representation

-

Component Architecture: Applications are built from nested, reusable components that:

- Encapsulate both UI elements and their behavior

- Can be composed into complex interfaces while maintaining separation of concerns

- Promote code reuse across different parts of an application or even across projects

- Enable teams to work independently on different components

These paradigms revolutionized how developers think about building user interfaces. Rather than focusing on manual DOM manipulation and event handling, modern frameworks encourage a more abstract, state-driven approach that is better suited to the complexity of contemporary web applications. This shift has enabled the development of increasingly sophisticated web experiences that rival native applications in functionality and responsiveness.

The evolution from jQuery to modern frameworks represents a fundamental shift in front-end development philosophy. While jQuery focused on simplifying interactions with the DOM, modern frameworks abstract the DOM away almost entirely, allowing developers to focus on application state and component composition. This evolution has enabled increasingly complex client-side applications while improving maintainability and development efficiency.

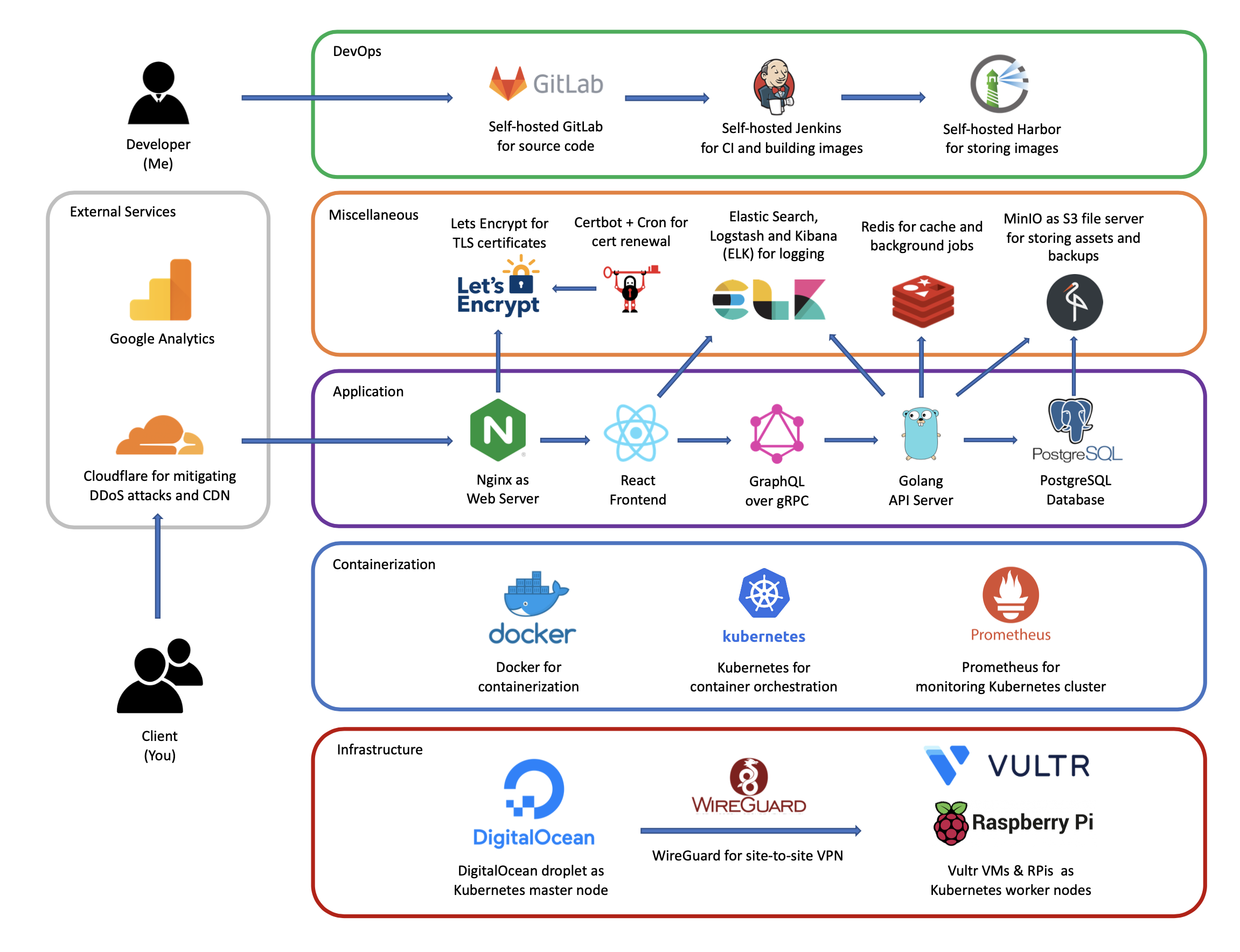

8. How Have Modern Backend Architectures Evolved? (2010-Present)

While frontend technologies were undergoing revolutionary changes, backend architectures were also evolving dramatically. The monolithic server-side applications of the early web gave way to more modular, scalable, and specialized approaches.

What Impact Did Node.js Have on Server-Side Development?

Node.js, created by Ryan Dahl in 2009, represented a paradigm shift in server-side development. For the first time, JavaScript—previously confined to browsers—could run on the server. This innovation allowed developers to use the same language across the entire stack, simplifying development and enabling code sharing between frontend and backend [RiseUp Labs].

Node.js introduced several transformative concepts:

- Event-driven, non-blocking I/O: Unlike traditional servers that allocated a thread per connection, Node.js used an event loop to handle multiple connections concurrently without blocking. This approach made it extremely efficient for I/O-intensive operations like handling web requests.

- JavaScript everywhere: Using the same language on client and server reduced context-switching for developers and enabled code sharing across environments.

- NPM ecosystem: Node's package manager created an unprecedented ecosystem of reusable modules, accelerating development through code sharing.

- Microservices support: Node.js's lightweight nature made it ideal for the emerging microservices architecture pattern.

Node.js quickly gained adoption for APIs, real-time applications, and microservices. Frameworks like Express.js provided lightweight, flexible tools for building web servers, while specialized frameworks for real-time communication (Socket.io) and full-stack development (Meteor) expanded Node's capabilities further [Medium].

How Did API-First Design Transform Backend Architecture?

As frontend frameworks became more powerful, the role of the backend shifted. Rather than generating complete HTML pages, modern backends increasingly focus on providing structured data through APIs (Application Programming Interfaces). This API-first approach decouples the frontend and backend, allowing them to evolve independently [cesarsotovalero.net].

Key aspects of the API-first approach include:

- RESTful principles: Standardized HTTP methods and resource-oriented URLs provide a consistent interface for clients.

- JSON as the lingua franca: Lightweight, language-independent JSON format replaced XML as the preferred data interchange format.

- GraphQL innovation: Developed by Facebook in 2015, GraphQL allows clients to request exactly the data they need, reducing over-fetching and under-fetching problems of traditional REST APIs.

- API documentation and standards: Tools like Swagger/OpenAPI, API Blueprint, and RAML improved documentation and consistency.

- API gateways: Specialized services for managing, securing, and optimizing API traffic emerged as API use grew.

// Modern Node.js API example with Express

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

app.use(express.json());

app.get('/api/users', async (req, res) => {

const users = await database.getUsers();

res.json(users);

});

app.post('/api/users', async (req, res) => {

try {

const newUser = await database.createUser(req.body);

res.status(201).json(newUser);

} catch (error) {

res.status(400).json({ error: error.message });

}

});

app.listen(3000, () => console.log('API server running on port 3000'));What Are Microservices and How Have They Changed Web Architecture?

Microservices architecture emerged around 2011-2012 as a response to the limitations of monolithic applications. Instead of building a single, integrated application, the microservices approach breaks functionality into small, specialized services that communicate through well-defined APIs.

This architectural shift offers several advantages:

- Independent development and deployment: Teams can work on different services simultaneously and deploy updates without affecting the entire system.

- Technology diversity: Different services can use the most appropriate languages and frameworks for their specific requirements.

- Targeted scaling: High-demand services can be scaled independently without scaling the entire application.

- Failure isolation: Problems in one service are less likely to cascade throughout the entire system.

- Easier maintenance: Smaller codebases are generally easier to understand, test, and maintain.

Microservices architecture has been widely adopted by technology leaders like Amazon, Netflix, Uber, and Spotify. It has proven particularly valuable for large-scale, complex applications that need to evolve rapidly and handle significant traffic. However, it introduces new challenges in service discovery, inter-service communication, distributed data management, and monitoring that have spawned entire ecosystems of supporting tools and technologies.

The evolution of backend architectures reflects a broader trend toward specialization, modularity, and loose coupling in modern web development. By separating concerns and establishing clear interfaces between components, these approaches enable greater scale, flexibility, and development velocity—essential qualities for today's dynamic web applications.

9. How Have Databases Evolved to Support Modern Dynamic Websites?

The increasing complexity and scale of dynamic websites drove significant evolution in database technologies. Traditional relational databases were joined by a diverse ecosystem of specialized storage solutions, each optimized for particular use cases.

What Drove the Rise of NoSQL Databases?

The term "NoSQL" (originally meaning "Not only SQL") emerged around 2009 to describe a growing category of non-relational database systems. These databases arose in response to limitations of traditional SQL databases when faced with the challenges of web-scale applications [MongoDB]:

- Scale: Many web applications needed to handle data volumes and traffic that strained relational databases' capabilities.

- Schema flexibility: Rapidly evolving web applications needed to modify data structures quickly without complex migrations.

- Geographic distribution: Global web services required data to be available across multiple regions with low latency.

- Specialized data models: Some applications needed database optimizations for specific data types or access patterns.

Different types of NoSQL databases emerged to address specific needs:

NoSQL Database Categories

| Type | Data Model | Key Advantages | Examples | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document | Semi-structured documents (JSON, BSON) | Schema flexibility, intuitive data model | MongoDB, CouchDB | Content management, catalogs, user profiles |

| Key-Value | Simple key-value pairs | Extreme performance, high throughput | Redis, DynamoDB | Caching, session storage, shopping carts |

| Column-Family | Tables with dynamic columns | Scalability for massive datasets | Cassandra, HBase | Time-series data, recommender systems |

| Graph | Nodes and relationships | Relationship traversal performance | Neo4j, JanusGraph | Social networks, recommendation engines |

NoSQL databases fundamentally changed how developers model and interact with data in web applications. Instead of forcing all data into normalized tables connected by relationships, NoSQL allowed data models to be tailored to application access patterns, often emphasizing denormalization and aggregation for performance.

How Did Database-as-a-Service Change Web Development?

The cloud computing revolution of the 2010s brought another significant shift in database usage: Database-as-a-Service (DBaaS). Rather than installing, configuring, and managing database servers themselves, developers could now use fully managed database services provided by cloud platforms [rapydo.io].

This shift offered numerous advantages for dynamic website development:

- Reduced operational burden: Cloud providers handled patching, backups, high availability, and other operational tasks.

- Scalability: Databases could scale up or down based on demand, often automatically.

- Global distribution: Cloud databases could replicate data across regions for lower latency and higher resilience.

- Specialized capabilities: Cloud providers offered purpose-built databases for specific use cases (time series, in-memory, etc.).

- Integration: Cloud databases integrated seamlessly with other cloud services for authentication, monitoring, and data processing.

Major cloud providers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure now offer dozens of specialized database services. This diversity allows developers to select the optimal data store for each component of their application rather than forcing all data into a single database system.

What Is the Polyglot Persistence Approach?

The proliferation of database options led to the concept of "polyglot persistence"—using multiple specialized databases within a single application, each chosen for its specific strengths. Rather than debating "SQL vs. NoSQL," modern applications often use both, along with other specialized data stores [CockroachLabs].

A typical modern web application might use:

- A relational database for transactional data requiring ACID guarantees

- A document database for flexible, evolving content structures

- A key-value store for caching and session management

- A search engine database for full-text search capabilities

- A graph database for relationship-intensive features

- A time-series database for metrics and monitoring

This diversity introduces complexity in data consistency and management but allows each part of the application to use the most appropriate tool for its specific requirements. Modern architectural patterns like microservices facilitate this approach by allowing different services to use different databases.

The evolution of database technologies has significantly expanded what's possible in dynamic websites. Features like real-time updates, personalization, sophisticated search, and global availability all benefit from the specialized capabilities of modern database systems. As web applications continue to grow in complexity and scale, database technology continues to evolve to meet these demands, with recent innovations in distributed SQL, vector databases for AI applications, and edge databases for low-latency global access.

10. What Are the Modern Architectures Powering Today's Dynamic Websites?

The architecture of dynamic websites has evolved dramatically from the monolithic approaches of the early web. Today's most innovative websites are built on architectures designed for performance, scalability, developer productivity, and enhanced user experiences.

How Has the LAMP Stack Evolved into the MEAN and MERN Stacks?

The LAMP stack (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP) dominated web development in the 2000s, but as JavaScript became more powerful both in browsers and on servers, new full-stack JavaScript architectures emerged. The MEAN stack—MongoDB, Express.js, Angular, and Node.js—represented a significant evolution, using JavaScript throughout the entire application stack [TechTarget].

Key differences between LAMP and MEAN include:

- Language consistency: MEAN uses JavaScript everywhere, eliminating the context switch between languages.

- Data format: JSON becomes the native data format throughout the stack, from database to client.

- Frontend approach: MEAN embraces client-side rendering and single-page application architecture.

- Database paradigm: MongoDB's document model replaces MySQL's relational model, offering schema flexibility.

- Server architecture: Node.js's event-driven approach differs fundamentally from Apache's thread/process model.

As React gained popularity, a variation called the MERN stack (MongoDB, Express.js, React, Node.js) emerged. Both MEAN and MERN stacks support modern, JavaScript-centric development workflows that can deliver highly interactive user experiences [Medium].

What Is JAMstack Architecture and Why Is It Popular?

JAMstack (JavaScript, APIs, Markup) emerged around 2015 as a modern architecture for building websites with improved performance, security, and developer experience. Unlike traditional architectures that generate HTML on the server for each request, JAMstack pre-builds pages at deploy time and serves them from CDNs, with client-side JavaScript and APIs providing dynamic functionality [Radixweb].

The core principles of JAMstack include:

- Pre-rendering: Pages are generated ahead of time during the build process, not on-demand.

- Decoupling: Frontend is completely separated from backend services.

- CDN delivery: Pre-built files are served from global CDNs for optimal performance.

- APIs for dynamic data: JavaScript calls APIs for any dynamic content or functionality.

- Microservices and serverless: Backend functionality is typically provided through specialized APIs and serverless functions.

JAMstack offers several significant advantages:

- Performance: Pre-built files served from CDNs load extremely quickly.

- Security: The reduced attack surface of static files improves security.

- Scalability: CDN-based delivery scales effortlessly to handle traffic spikes.

- Developer experience: Clear separation of concerns and modern tooling improve productivity.

- Cost efficiency: Hosting static files is typically less expensive than running application servers.

Popular JAMstack implementations use static site generators (Gatsby, Next.js, Hugo, Jekyll) combined with headless CMS systems for content management and serverless functions for dynamic features. This architecture has been particularly popular for content-focused websites, marketing sites, and applications where performance is critical [CodeTV].

How Are Serverless Architectures Changing Dynamic Websites?

Serverless architecture represents another significant evolution in how dynamic websites are built and deployed. Despite the name, serverless doesn't mean "no servers"—rather, it abstracts server management away entirely, allowing developers to focus on writing code while cloud providers handle all infrastructure concerns [Google Cloud].

Key characteristics of serverless architectures include:

- Functions as a Service (FaaS): Code runs as individual functions triggered by events rather than as long-running applications.

- Auto-scaling: Functions scale automatically from zero to thousands of concurrent executions based on demand.

- Pay-per-execution: Billing is based on actual function executions, not on provisioned capacity.

- Statelessness: Functions don't maintain state between executions, requiring external storage for persistent data.

- Event-driven: Functions typically respond to events (HTTP requests, database changes, message queue items, etc.).

// AWS Lambda serverless function example

exports.handler = async (event) => {

// Process an API request

const userId = event.pathParameters.userId;

// Fetch user data from database

const userData = await dynamoDB.get({

TableName: "Users",

Key: { userId: userId }

}).promise();

// Return response

return {

statusCode: 200,

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: JSON.stringify(userData.Item)

};

};Serverless architectures have gained rapid adoption for dynamic websites due to several compelling benefits:

- Reduced operational complexity: No server management, patching, or capacity planning required.

- Cost efficiency: No charges for idle capacity; costs scale directly with usage.

- Built-in high availability: Cloud providers handle redundancy and failover automatically.

- Developer focus: Teams can focus on business logic rather than infrastructure concerns.

- Rapid iteration: Individual functions can be deployed independently, enabling faster development cycles.

Typical serverless web applications combine static assets delivered via CDNs (following JAMstack principles) with serverless functions providing API endpoints for dynamic functionality. This approach has proven particularly effective for applications with variable traffic patterns, where traditional server provisioning would result in either over-provisioning (wasted resources) or under-provisioning (performance issues) [StudioLabs].

Modern web architectures emphasize decoupling, specialized components, and managed services over monolithic applications running on self-managed servers. These approaches improve performance, scalability, and developer productivity while reducing operational burden—all crucial factors in the increasingly competitive landscape of dynamic websites. As the web continues to evolve, we can expect further architectural innovations focused on edge computing, global distribution, and seamless integration of advanced capabilities like AI.

11. How Has Mobile Technology Transformed Dynamic Websites?

The explosive growth of mobile internet usage has fundamentally changed how dynamic websites are designed, developed, and delivered. Adapting to the constraints and opportunities of mobile devices has driven significant innovations in web technologies and approaches.

Why Was Responsive Web Design a Revolutionary Approach?

When smartphones first gained popularity in the late 2000s, most websites offered separate mobile versions (often on "m." subdomains) with limited functionality. This approach required maintaining multiple codebases and created a fragmented user experience. In 2010, web designer Ethan Marcotte introduced the concept of "responsive web design" in an influential article for A List Apart [W3Schools].

Responsive design represented a fundamental shift in approach. Rather than creating different sites for different devices, it proposed a single, flexible design that could adapt to any screen size. This approach relied on three key technical components:

- Fluid grids: Using relative units (percentages) rather than fixed pixels for layout elements.

- Flexible images: Ensuring images scale appropriately within their containing elements.

- Media queries: Using CSS conditionals to apply different styles based on device characteristics.

/* Example of responsive design with media queries */

.container {

width: 100%;

max-width: 1200px;

margin: 0 auto;

}

.column {

width: 33.333%;

float: left;

padding: 1em;

}

/* Tablet styles */

@media screen and (max-width: 768px) {

.column {

width: 50%;

}

}

/* Mobile styles */

@media screen and (max-width: 480px) {

.column {

width: 100%;

float: none;

}

}Responsive design offered several significant advantages:

- Unified codebase: A single HTML source served all devices, simplifying maintenance.

- Future-friendly: The approach adapted to new device sizes without requiring redesigns.

- Consistent experience: Users encountered the same content and features regardless of device.

- SEO benefits: A single URL for all devices improved search engine optimization.

- Cost efficiency: Development and maintenance costs were lower than for separate mobile sites.

By 2013, responsive design had become the industry standard approach for accommodating the growing diversity of devices accessing the web. Its principles continue to influence modern web development, though they have evolved and been supplemented by additional techniques [FinalSite].

What Is the Mobile-First Approach to Web Development?

As mobile usage continued to grow—eventually surpassing desktop usage around 2016—the "mobile-first" approach emerged as a refinement of responsive design. First popularized by Luke Wroblewski in his 2011 book "Mobile First," this methodology advocated designing for mobile devices first, then progressively enhancing the experience for larger screens.

Mobile-first design inverted the traditional process:

- Start with mobile constraints: Design for the smallest screens and slowest connections first.

- Progressive enhancement: Add features and complexity as screen size increases.

- Performance focus: Optimize for speed and efficiency from the beginning.

- Content prioritization: Identify the most critical content and functionality for mobile users.

This approach aligned with the realities of modern web usage, where mobile often represents the majority of traffic for many websites. It also addressed practical issues like performance more effectively by making it a fundamental consideration rather than an afterthought.

Mobile-first design principles have been incorporated into major frameworks and design systems like Google's Material Design and Bootstrap 4+, which adopted a mobile-first approach to their grid systems and components [MDN Web Docs].

How Have Progressive Web Apps Changed the Mobile Web Experience?

Progressive Web Apps (PWAs), introduced by Google in 2015, represent the next evolution in mobile web development. PWAs combine the reach of the web with capabilities traditionally associated with native mobile applications, creating experiences that are reliable, fast, and engaging.

Key characteristics of PWAs include:

- Progressive: Work for every user, regardless of browser choice.

- Responsive: Fit any form factor: desktop, mobile, tablet, or whatever is next.

- Connectivity independence: Function offline or with poor network conditions.

- App-like interface: Feel like an app with app-style interactions and navigation.

- Fresh: Always up-to-date thanks to service worker update processes.

- Safe: Served via HTTPS to prevent snooping and content tampering.

- Discoverable: Identifiable as "applications" by search engines.

- Re-engageable: Make re-engagement easy through features like push notifications.

- Installable: Allow users to add to their home screen without an app store.

- Linkable: Easily shared via URL, without complex installation.

Core Technologies Behind Progressive Web Apps

- Service Workers: JavaScript scripts that run in the background, enabling features like offline support and push notifications.

- Web App Manifest: JSON file that provides information about the application (name, icons, etc.) needed for installation.

- HTTPS: Secure connections are required for PWAs, ensuring data security and enabling features like service workers.

- Responsive Design: PWAs must work across all device sizes, building on responsive design principles.

- App Shell Architecture: Separating application interface from content for faster loading and reliable offline experiences.

PWAs have been widely adopted by major companies like Twitter (Twitter Lite), Starbucks, Pinterest, Uber, and others, who have reported significant improvements in engagement, conversion rates, and performance compared to both traditional websites and native apps. For many organizations, PWAs offer a compelling middle ground between the reach of the web and the capabilities of native applications [GeeksforGeeks].

The evolution from separate mobile sites to responsive design to PWAs reflects the web's adaptation to the central role of mobile devices in modern internet usage. These approaches have collectively transformed dynamic websites from desktop-centric experiences to truly multi-device platforms that can deliver compelling experiences regardless of how users access them. As mobile technology continues to evolve, we can expect further innovations that continue to blur the lines between web and native experiences while leveraging the web's unique strengths of reach, linkability, and low-friction access.

12. How Did Real-Time Technologies Enhance Dynamic Websites?

Traditional web interactions followed a request-response pattern: the client makes a request, the server responds, and the connection closes. This model worked well for document-based content but proved limiting for applications requiring immediate updates or continuous data streams. Real-time web technologies addressed this limitation, enabling dynamic websites to provide instantaneous updates and interactive experiences.

What Are WebSockets and How Did They Change Web Communications?

WebSockets, standardized in 2011 (RFC 6455), introduced a fundamental change to web communications. Unlike the traditional HTTP model, WebSockets establish a persistent, bidirectional connection between client and server, allowing data to flow in either direction at any time without the overhead of establishing new connections [Ably].

Key characteristics of WebSockets include:

- Persistent connection: Once established, the connection remains open until explicitly closed by either party.

- Full-duplex communication: Data can flow in both directions simultaneously.

- Low latency: Without the overhead of establishing new connections, data transfer is nearly instantaneous.

- Efficiency: Minimal header information after the initial handshake reduces bandwidth usage.

- Native browser support: Modern browsers provide built-in WebSocket APIs.

// WebSocket client example

const socket = new WebSocket('wss://example.com/socket');

// Connection opened

socket.addEventListener('open', (event) => {

socket.send('Hello Server!');

});

// Listen for messages

socket.addEventListener('message', (event) => {

console.log('Message from server:', event.data);

});

// Connection closed

socket.addEventListener('close', (event) => {

console.log('Connection closed');

});WebSockets enabled a new generation of web applications with real-time capabilities that were previously impractical or impossible:

- Live chat applications: Messages appear instantly without refreshing or polling.

- Collaborative editing tools: Multiple users can see each other's changes in real time.

- Live dashboards: Metrics and visualizations update continuously as data changes.

- Multiplayer games: Players interact in real time within the browser.

- Financial and sports tickers: Price and score updates appear instantly.

Libraries like Socket.IO emerged to simplify WebSocket implementation and provide fallbacks for browsers or networks that didn't support WebSockets. These tools made real-time features accessible to more developers and applications [RxDB].

What Are Server-Sent Events (SSE) and How Do They Differ from WebSockets?

Server-Sent Events (SSE) emerged as a simpler alternative to WebSockets for scenarios requiring real-time updates in one direction only—from server to client. Standardized as part of HTML5, SSE uses a long-lived HTTP connection to send messages from the server to the client [MDN Web Docs].

Key differences between SSE and WebSockets include:

| Feature | WebSockets | Server-Sent Events |

|---|---|---|

| Communication direction | Bidirectional (client-to-server and server-to-client) | Unidirectional (server-to-client only) |

| Protocol | ws:// or wss:// (custom protocol) | http:// or https:// (standard HTTP) |

| Reconnection | Must be implemented manually | Automatic reconnection built-in |

| Message types | Binary and text | Text only |

| Cross-origin support | CORS must be implemented | CORS supported by default |

| Maximum connections | Varies by browser, typically higher | Limited by HTTP connection limit |

SSE offers several advantages for specific use cases:

- Simplicity: Uses standard HTTP, making it easier to implement and debug.

- Built-in reconnection: Handles network interruptions automatically.

- Compatibility: Works with standard HTTP infrastructure like proxies and load balancers.

- Event naming: Supports named events for more structured data handling.

SSE has proven particularly useful for applications like news tickers, stock updates, social media feeds, and notification systems where the primary information flow is from server to client. Its simplicity makes it an attractive option when full WebSocket functionality isn't required [Dev.to].

How Have These Technologies Enabled New Types of Web Applications?

Real-time web technologies have expanded the types of applications that can be delivered through the browser, enabling experiences that were previously limited to native applications:

Real-Time Web Application Categories

- Communication Tools: Video conferencing, instant messaging, and virtual meeting platforms like Slack, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet leverage WebSockets and WebRTC for real-time audio, video, and text communication.

- Collaborative Applications: Document editors like Google Docs, Notion, and Figma use real-time synchronization to allow multiple users to work on the same content simultaneously, seeing each other's changes as they happen.

- Live Entertainment: Streaming platforms, interactive webinars, and live events utilize real-time technologies to deliver content and enable audience participation.

- Financial Applications: Trading platforms, banking dashboards, and cryptocurrency exchanges rely on instant updates for time-sensitive financial information.

- IoT Interfaces: Monitoring and control systems for Internet of Things devices use real-time communication to provide current status and immediate control.

- Gaming: Browser-based multiplayer games leverage WebSockets for synchronized gameplay experiences.

These technologies have fundamentally changed user expectations for dynamic websites. Where users once accepted page refreshes and manual updates as normal, they now expect instant reactions and live updates. This shift has pushed developers to adopt architectures and practices that support real-time functionality as a core capability rather than an add-on feature.

Beyond specific applications, real-time technologies have broader implications for how we interact with information online. They enable a more continuous, stream-based model of information consumption where data flows to users as it becomes available, rather than requiring them to explicitly request updates. This model aligns more closely with how information exists in the real world—continuously changing rather than existing in discrete, static snapshots.

As internet connectivity continues to improve and browser capabilities expand, we can expect real-time features to become even more prevalent in dynamic websites. Emerging standards like WebTransport and WebRTC data channels promise to further enhance real-time capabilities, enabling even more sophisticated interactive experiences in the browser.

13. What Are the Emerging Trends Shaping Dynamic Websites?

The evolution of dynamic websites continues at a rapid pace, with several emerging technologies poised to transform how we build and interact with the web. These innovations promise to make websites more powerful, intelligent, and seamlessly integrated with our daily lives.

How Is WebAssembly Extending What's Possible in the Browser?

WebAssembly (Wasm) represents one of the most significant advancements in browser technology in recent years. First released in 2017 as a collaboration between major browser vendors, WebAssembly is a binary instruction format that allows code written in languages like C, C++, Rust, and Go to run in the browser at near-native speed [cesarsotovalero.net].

Key capabilities of WebAssembly include:

- Performance: Code executes at near-native speed, enabling computationally intensive applications in the browser.

- Language flexibility: Developers can use languages optimized for performance or specific domains rather than only JavaScript.

- Portability: The same binary can run across different browsers and platforms.

- Security: Execution occurs in a sandboxed environment with strong isolation from the host system.

- Integration: WebAssembly modules can interoperate seamlessly with JavaScript and web APIs.

These capabilities are enabling entirely new categories of web applications that were previously impractical due to performance constraints [e-spincorp]:

- Graphics-intensive applications: Games, 3D visualization tools, and CAD software can achieve console-quality graphics in the browser.

- Computationally demanding tools: Video and audio editing, scientific simulations, and machine learning can run efficiently client-side.

- Ported desktop applications: Existing applications written in languages like C++ can be compiled to WebAssembly and delivered via the web.

- Performance-critical libraries: Key components of web applications can be implemented in WebAssembly for improved performance while maintaining a JavaScript interface.

WebAssembly is still evolving, with upcoming features like threading, garbage collection, and direct DOM access promising to further expand its capabilities. As it matures, we can expect WebAssembly to enable increasingly sophisticated applications that blur the line between web and native experiences [DevPumas].

What Role Is AI Playing in Modern Dynamic Websites?

Artificial Intelligence is rapidly becoming integrated into dynamic websites, transforming how they function, adapt, and interact with users. AI capabilities are being applied across all aspects of web development and user experience [Adrian Lacy Consulting]:

AI Applications in Dynamic Websites

- Personalization: AI algorithms analyze user behavior, preferences, and context to dynamically customize content, layouts, and recommendations, creating uniquely tailored experiences for each visitor.

- Conversational Interfaces: Chatbots and virtual assistants powered by natural language processing provide interactive, context-aware support and information retrieval without human intervention.

- Content Generation: AI systems can automatically generate or adapt content, from product descriptions and blog posts to translations and summaries, enabling dynamic content at scale.

- Visual Recognition: Computer vision capabilities enable advanced image searching, automatic tagging, visual product recognition, and accessibility features for visually impaired users.

- Predictive Analytics: AI models can anticipate user needs and behaviors, enabling proactive features like predictive search, inventory management, and personalized notifications.

- Automated Design: AI-assisted design tools can generate layouts, color schemes, and visual elements optimized for specific goals and user preferences.

The integration of AI into websites is accelerating with the development of specialized models designed to run efficiently in the browser. Technologies like TensorFlow.js allow machine learning models to run client-side, enabling privacy-preserving AI features that don't require sending sensitive data to servers. This trend toward "edge AI" aligns with broader privacy concerns and the desire for low-latency experiences [Innervate].

As AI capabilities continue to advance and become more accessible, we can expect dynamic websites to become increasingly intelligent and adaptive. The line between static content and dynamic, AI-driven experiences will blur, with websites functioning more like intelligent assistants that anticipate and respond to user needs in real-time.

How Is Edge Computing Transforming Website Architecture?

Edge computing represents a significant shift in how dynamic websites are delivered, moving processing and logic closer to end users rather than centralizing it in distant data centers. This approach distributes computing resources across a network of edge nodes located in points of presence (POPs) around the world [Gcore].

Key benefits of edge computing for dynamic websites include:

- Reduced latency: Processing occurs physically closer to users, minimizing round-trip time for requests.

- Improved performance: Dynamic content can be generated or customized at the edge without trips to origin servers.

- Scalability: Edge networks distribute load across many locations, handling traffic spikes more effectively.

- Resilience: Distributed architecture reduces single points of failure and improves availability.

- Reduced bandwidth: Processing at the edge can minimize data transfer between edge nodes and origin servers.

Edge computing is enabling new approaches to building dynamic websites:

- Edge functions: Serverless functions that run at the edge can perform authentication, personalization, A/B testing, and other dynamic operations with minimal latency.

- Edge rendering: Server-side rendering can occur at edge locations rather than in central data centers, combining the SEO benefits of server rendering with the performance of edge delivery.

- Edge databases: Distributed database systems with edge caching and synchronization enable low-latency data access worldwide.

- Dynamic edge caching: Advanced caching strategies can store and serve personalized content from the edge based on user context.

Platforms like Cloudflare Workers, Fastly Compute@Edge, and Vercel Edge Functions are making these capabilities accessible to developers without requiring specialized infrastructure knowledge. This democratization of edge computing is accelerating its adoption and driving innovation in dynamic website architectures [Venture Magazine].

The future of dynamic websites lies in increasingly distributed architectures that leverage the edge for both delivery and computation. This evolution will continue to improve performance and user experience while reducing the operational complexity traditionally associated with global-scale applications.

What Other Trends Are Emerging in Dynamic Website Development?

Several additional trends are shaping the evolution of dynamic websites:

- Headless architectures: The separation of frontend presentation from backend content management continues to gain momentum, with headless CMS systems enabling more flexible content delivery across multiple channels and interfaces [Webstacks].

- Web Components: The adoption of standardized, framework-agnostic components promises greater interoperability and longevity for UI elements, reducing dependence on specific JavaScript frameworks [Chrome for Developers].

- Enhanced privacy features: As privacy regulations tighten and browsers restrict tracking capabilities, websites are evolving to provide personalized experiences while respecting user privacy through techniques like edge computing, first-party data, and on-device processing.

- Immersive web experiences: Technologies like WebXR are enabling augmented and virtual reality experiences directly in the browser, creating new possibilities for interactive content, virtual showrooms, and immersive storytelling [Digital Silk].

- API-first design: The continued growth of API-centric development approaches is leading to more modular, composable websites built from specialized services combined through well-defined interfaces.

- Low-code/no-code platforms: Tools that enable non-developers to create dynamic websites are becoming increasingly sophisticated, democratizing web development while integrating with professional developer workflows [WP Engine].

These trends collectively point toward a future where dynamic websites are more intelligent, performant, and accessible to both developers and users. The web platform continues to evolve as a universal application delivery mechanism, gradually acquiring capabilities once exclusive to native applications while maintaining its unique strengths of reach, compatibility, and immediate access.

14. Frequently Asked Questions About Dynamic Websites

What's the difference between static and dynamic websites?

Static websites consist of fixed HTML files that remain the same for every user until manually updated. Dynamic websites, in contrast, generate content on-demand based on various factors like user input, database queries, or external APIs. While static sites are simpler and faster to load, dynamic sites offer personalization, user interaction, and content that can change without developer intervention. Modern approaches like JAMstack blur this distinction by pre-building static files that incorporate dynamic functionality through JavaScript and APIs.

When should I use a CMS versus a custom-built dynamic website?

Content Management Systems (CMS) like WordPress, Drupal, or Contentful are ideal when content management is the primary concern, non-technical users need to update content frequently, and standard features like blogs, user management, or e-commerce are sufficient. Custom-built dynamic websites are more appropriate for unique functionality requirements, specialized performance needs, complex integrations with other systems, or when security and compliance demands require complete control over the codebase. Many projects take a hybrid approach, using a headless CMS for content management while custom-building the frontend and specialized functionality.

How do I optimize performance for dynamic websites?

Performance optimization for dynamic websites involves multiple strategies: implement caching at various levels (browser, CDN, application, database); optimize database queries with proper indexing and query design; use asynchronous processing for non-critical operations; minimize HTTP requests through bundling and code splitting; optimize images and media with compression and responsive techniques; utilize CDNs for global distribution; consider edge computing for dynamic operations near users; implement lazy loading for off-screen content; and monitor performance with tools like Lighthouse or WebPageTest to identify specific bottlenecks.

What are the security considerations specific to dynamic websites?

Dynamic websites face several security challenges: injection attacks (SQL, XSS, CSRF) must be prevented through input validation, parameterized queries, and output encoding; authentication systems need protection against brute force and session hijacking; data must be encrypted both in transit (HTTPS) and at rest; regular security updates for all components are essential; access controls should follow the principle of least privilege; API endpoints require rate limiting and authentication; third-party dependencies should be regularly audited; and comprehensive security testing (both automated and manual) should be conducted regularly. Modern security approaches also include Content Security Policy (CSP), security headers, and Web Application Firewalls (WAF).

How do I choose between server-side rendering (SSR) and client-side rendering (CSR)?

The choice between SSR and CSR depends on your specific requirements. Server-side rendering excels at initial page load performance, SEO (as search engines see complete content immediately), and supporting users with JavaScript disabled or on low-powered devices. Client-side rendering offers richer interactivity, reduced server load, faster subsequent navigation, and a more app-like experience. Many modern applications use hybrid approaches like static site generation with hydration or incremental static regeneration, combining the benefits of both methods. Frameworks like Next.js, Nuxt.js, and Gatsby provide tools for implementing these hybrid approaches efficiently.

What's the future of dynamic websites with the rise of mobile apps?

Despite the popularity of mobile apps, dynamic websites maintain significant advantages: they're accessible across all devices without installation, discoverable through search engines, easily shareable via links, and updateable without app store approval processes. The future lies in technologies that combine these web advantages with app-like experiences, particularly Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) that offer offline functionality, push notifications, and home screen installation. As web capabilities continue to expand through APIs like WebAssembly, WebXR, and advanced device access, the distinction between web and native applications will continue to blur, with dynamic websites becoming increasingly powerful while maintaining their inherent advantages.

How is AI changing dynamic website development?

AI is transforming dynamic websites in several ways: personalization engines create tailored experiences based on user behavior and preferences; chatbots and virtual assistants provide conversational interfaces; content can be automatically generated, summarized, or adapted; visual recognition enables advanced image search and accessibility features; predictive analytics anticipate user needs; and automated design tools can generate layouts and visual elements. AI is also enhancing development itself through code generation, bug detection, and automated testing. As edge AI capabilities improve, more intelligence can run directly in the browser, enabling sophisticated features with lower latency and better privacy preservation. These technologies collectively enable more adaptive, responsive websites that can understand and anticipate user needs.

What's the relationship between APIs and dynamic websites?

APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) have become fundamental to modern dynamic websites, enabling modular architecture where specialized services handle specific functions. Internal APIs connect different components of a website, allowing the frontend to request data and functionality from backend services. External APIs integrate third-party services like payment processors, mapping tools, or social media platforms. The API-first approach—designing APIs before implementing interfaces—has become a best practice, enabling multiple frontends (web, mobile, IoT) to share the same backend services. Modern architectures like JAMstack leverage APIs extensively, with static frontends consuming dynamic data through API calls. This decoupling increases flexibility, scalability, and development efficiency.

15. Key Takeaways and Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Evolutionary Journey: Dynamic websites have evolved from simple CGI scripts in 1993 to sophisticated applications powered by modern frameworks, serverless architectures, and AI technologies.

- Server-Side Evolution: Server technologies progressed from CGI to specialized languages (PHP, ASP, JSP) to modern API-driven backends and microservices architectures that prioritize scalability and developer experience.

- Client-Side Revolution: JavaScript evolved from simple form validation to powerful frameworks (React, Angular, Vue) enabling complex, application-like experiences running directly in the browser.